Site Under Development, Content Population and SEO, Soft Launch 1st January 2020

Autoimmune encephalitis (AIE) must be diagnosed as early as possible to facilitate appropriate treatment. This group of conditions presents in various ways, with subacute memory loss, altered cognition, seizures, abnormal movements and behavioral or psychiatric aberrations. Other signs and symptoms may be present depending on the areas of the brain affected and the severity of the illness.

The diagnosis might be easy in several cases if autoantibody testing was universally available, was accurate and cost-effective for all possible autoantibodies, and if they could always be detected in these conditions. Unfortunately, this is not the case and up to a third of patients may not show any autoantibodies that are detectable by available tests, despite a clinical picture of AIE.

These tests also take several weeks to return results, which is time lost for treatment. Even a positive result may not confirm the immune etiology. Clinical trials with immunotherapy may not be feasible in all settings, given that many centers may not offer the resources for such intensive or expensive therapy in the absence of an established diagnosis as an indication.

Also, immunotherapy may help to produce symptom remission even in other conditions such as primary CNS lymphoma, so that its success need not confirm the diagnosis of AIE.

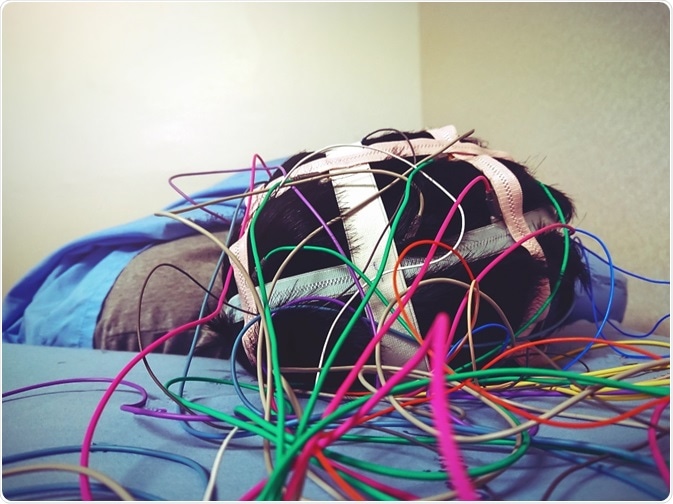

For this reason, it is necessary to make a clinical diagnosis early in a logical manner to allow the patient to gain access to the best available treatment. Such a process will depend upon a standard full neurologic assessment and diagnostic imaging with electroencephalogram (EEG) testing.

A patient may be said to be possibly suffering from AIE if all three of the criteria below are met:

MRI imaging of the brain is usually nonspecific, or even normal, but limbic encephalitis usually produces some characteristic changes in the medial temporal lobe. EEG testing is also nonspecific except for the extreme delta brush pattern seen in some cases of NMDAR encephalitis, but it may help rule out other disorders, or show the presence of some special seizure disorders such as subclinical seizures, or non-convulsive status epilepticus.

A detailed history should be repeated if the suspicion of AIE is raised. It should be followed by a complete physical and neurologic examination, blood and cerebrospinal (CSF) testing for routine parameters, and brain MRI.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis is an important cause of similar presentations, and should be ruled out by CSF PCR for HSV, which should be repeated a few days later if negative despite high clinical suspicion, as very early testing may result in false negatives. Other infections should also be ruled out depending on the history of travel exposure, for instance, and examination findings.

The demographic characteristics of the patient along with other illnesses (diarrhea, psychosis, ovarian teratoma), which may have preceded or occurred simultaneously with the encephalitis manifestations may give a clue as to the actual illness and should be carefully examined. If no particular syndrome is still identifiable, autoantibody testing must be proceeded to.

In disorders which present either clinically or by MRI with distinctive findings (such as limbic encephalitis, anti-NMDAR encephalitis), the diagnosis may be reasonably made.

In AIE autoantibody testing is very important, but may not be conclusive. Tests have been commercially developed to detect antibodies to NMDAR, LGI1, AMPAR, Caspr2, and GABA(b)R, but many others are not available. CSF sampling is necessary for accurate testing in NMDAR and other antigens bound to the cell surface, because serum testing has a low sensitivity and specificity.

IgG antibodies must be tested for, as anti-NMDAR IgM and IgA elevations do occur in psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia, and even in normal individuals, but not IgG.

In anti-NMDAR encephalitis, antibody titers fail to show the disease severity, and so once shown to be positive, clinical changes are more important than antibody titers to assess severity of illness and response to therapy, and even to detect a relapse.

Caspr2 and LGI1 are found in association with voltage-gated potassium channels (VGKC) which means the antibody to VGKC causes several proteins to clump, including the LGI1, Caspr2 and VGKC protein itself. This test is therefore not very significant for AIE in low titers, especially when detected in serum, unless confirmed by CSF LGI1 and Caspr2 antibody.

GAD65 is a nonspecific antibody found in a host of situations, including type 1 diabetes mellitus, stiff person syndrome (SPS), epileptic disorders and cerebellar degeneration. In low titers it may not represent true neurologic disease, especially in a diabetic patient.

However, new-onset type 1 diabetes in a patient with neurologic features and positive GAD65 antibodies may prompt a CSF GAD65 (and related autoantibody) testing.

Hashimoto’s encephalopathy is thought to be autoimmune, being an encephalopathy linked to thyroid autoantibodies, which remits with steroids or alternative immunotherapy. However, biological mechanisms for thyroid antibodies to be pathogenic to the brain are lacking, and the thyroid hormones are too subtly altered to pose a viable explanation.

Thus, the syndrome is not thought to be a true case, but should instead trigger testing to detect other autoantibodies, which may be responsible for the encephalitis symptoms. In the absence of positive results, immunotherapy should still be attempted if thought to be potentially beneficial.

Most brain imaging utilizes MRI once the suspicion of AIE is raised. In most cases of anti-NMDAR, AMPAR, LGI1, GABA(b)R and Caspr2, no specific finding is present, but a high T2 signal may be emitted by the medial temporal lobes. This however is not specific as the same may be seen in HSV encephalitis or other viral encephalitides. In short, it is not of much use in diagnosing AIE.

PET or SPECT imaging may show some areas to have increased metabolism, but a specific pattern is yet to be described for different syndromes.

An EEG helps, as already mentioned, to rule out subclinical seizures and determine the prognosis, particularly to help identify a certain condition. This is so with the extreme delta brush pattern seen in a third of patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis, especially when comatose, and which is pathognomonic of this illness.

It will lead to testing for NMDAR antibodies. Moreover, it is useful for monitoring patients with AIE who are showing long periods of abnormal behavior or are not responding to stimuli for alarming periods.

Again, it is of use in status epilepticus, which is especially high in incidence in the presence of anti-NMDAR, or anti-GABA(a) and anti-GABA(b) receptor antibodies, and which may not respond to ordinary treatments in the latter cases. Faciobrachial dystonic seizures are seen in anti-LGI1 encephalitis and may occur from weeks to months in advance of any other clinical features.

In several of the AIE the encephalitis is triggered by autoantibodies produced in response to a tumor elsewhere, as in anti-NMDAR or anti-Hu antibodies. Tumor detection is therefore an urgent and necessary task, both to treat the cancer and so prevent further antibody production, and to make sure that the immunotherapy does not interfere with cancer diagnosis or treatment at a later stage.

When antibodies are found in the CSF it is more significant for AIE and the most likely tumors should be diligently sought. Imaging techniques such as MRI, CT and PET may be appropriate when looking for lung tumors, ultrasound or MRI of the pelvis for ovarian teratomas, testicular scans for anti-Ma2 antibodies, mammography, breast MRI, Pap smear and pelvic ultrasound for anti-Yo antibodies.

If cerebellar degeneration is present the risk of a tumor is very high, about 90%, and intensive tumor screening should take place whether or not autoantibodies are detected. A negative screen should not prevent repeated testing as the size of the tumor may be initially undetectable. The intervals between repeat screening may increase, of course, as time goes on without detection.

Patients with no AIE syndromes, other autoimmune neurologic syndromes, and thyroid antibodies with features of encephalitis may be tentatively diagnosed as Hashimoto’s encephalopathy, provided they have no detectable neuronal antibodies and other causes for the encephalopathy are absent.